Fire and Rain: How Rain Impacted the NorCal Wildfires

Posted by on November 30, 2017 Data, Education, Opinion, Data Analytics

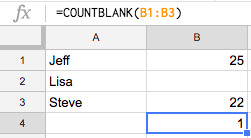

The 2017 Fire Season in Northern California was one of the most costly and deadly on record. When ranked against the yearly totals for the last 14 years, 2017 ranks as the most deadly, and is among the most costly in terms of Structures and Acreage Destroyed. These yearly totals are shown, on a logarithmic scaled Bar Chart below, across the entire state of California and isolated to the counties worst hit by the Late Summer Outbreak of 2017 in Northern California.

Climate in Northern California has a distinct impact on the plague of wildfires that seem to be a regular occurrence here. As you can see on the area chart below, the rainy season in Northern California is fairly distinct and lasts from roughly the beginning of October to the end of March. Then from late spring to early autumn there is a considerable drop in precipitation to almost none at all in July and August.

The drop in precipitation totals to almost none at all coincides directly with evidence of a “Fire Season” in the area. Also referred to as dry season, the fire season is when rains in the area almost disappear and certain wind and other weather phenomena lead to conditions in the area that are perfect for wildfires.

Predictably, the peaks in the “Fire Season” seem to come in the valley between peaks of the “Wet Season.” Winds coming in to the region from the arid desert and mountainous landscapes to the east dry out the area’s freshly grown vegetation, that spent the wet season in a abundance of moisture that helped lead to more, taller grass. Any number of natural or man made incidents could provide the spark that ignites the grass and before it can be contained it can burn out of control, causing the destruction we showed in the first graph.

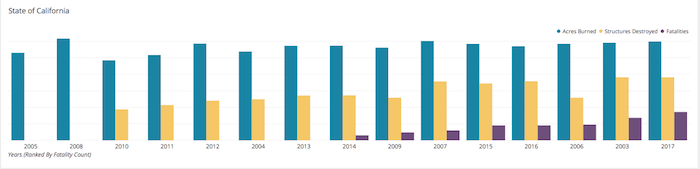

Another Data Study that might be interesting is to see how a particular rainy wet season might coincide with the following Fire Season. To do that we have created a horizontal bar chart and show it below. The rain totals are simply multiplied by -1 to get them to appear as a negative value to the fire values of the coinciding year. In this chart we are comparing the Wet Season with the following Fire Season, basing the spans of those seasons with our observations from above. What this means is that the 2017 Wet Season value will be the sum of all monthly precipitation totals from October 2016 to the end of March 2017 and the fire season will be the summations from July to November of 2017.

When sorted by the most rainy season to the least of our data set, the worst fire season does coincide with the rainiest season, but the trend does not follow exactly as one might expect. The 2nd and 3rd worst fire seasons are the 4th and 7th rainiest season respectively.

We can conclude from this data analysis that in the particular years and areas highlighted a more destructive fire season can follow a rainier season, but it’s not necessarily guaranteed. Also, the rain season does not contribute in a way that some kind of indicative factor might be gleaned. It is safe to say that the rainier season can contribute to a higher fire potential but does not necessarily a guarantee of a higher season and instead a combination of factors are at play.

What factors can you think of? Find a data set and tweet me an image of your data study, @timmiller716 on Twitter. Use the hashtag #wildfiredata.