The Power of Timely Decision Making

Posted by on April 4, 2016 Data Analytics

A study conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota found that ‘empowerment is a major motivator to employees.’ What lies at the very heart of empowerment is the freedom to make decisions. People want to do a good job and succeed. And, they do this best when they are trusted by leaders to take action, make changes and solve problems.

— Decision-Paralysis: Why It’s Prevalent And Three Ways To End It by David Sturt and Todd Nordstrom

I closed-out my first year after receiving my Bachelors Degree in command of a 3-person team, tasked to regularly go forward of most infantry assets in providing forward reconnaissance, all while carrying well over a couple million dollars-worth of “sensitive” communications gear. I was just a young kid thrust into an extraordinary situation based on the needs of his chain of command.

The business world of today is a far cry from the stresses of the modern battlefield. It’s considerably more beneficial to a person’s health and well-being than a tour in a combat zone, but there is one aspect that is constant in both environments: Decision-Paralysis – over-analyzing a situation to the point that a decision is never taken.

We’ve all been there before, whether it’s in a team meeting, the boardroom, or even in a restaurant choosing a meal. Many times, for both key stakeholders and entry-level “worker bees” alike, it’s due to not feeling like you have adequate authorization to effect change in your organization. Other times, it’s due to having too much information at your fingertips where you feel like you are being crushed under a mountainous mass of information. In the boardroom, it could cost millions but on the battlefield, it could cost lives.

In Decision-Paralysis: Why It’s Prevalent And Three Ways To End It, David Sturt and Todd Nordstrom come to the conclusion that the best way to ensure successful decisions are made in a timely manner is by decentralizing the decision-making process and empowering individual contributors to discover the appropriate problem solving conclusions, since they have the most interaction with the data involved.

This does two things:

-

By showing that you trust the team to make appropriate and timely decisions, it builds the confidence of the team member and allows them the autonomy to exceed expectations they might have not thought possible.

-

By decentralizing the decision-making process to key teams/stakeholders in your organization, you are available to address other issues or spend more time on those issues that require extra attention.

However, a survey done by consultancy firm Head, Heart and Brain, found that 47% of employees surveyed feel “actively threatened” by their supervisors while Harvard Business Review found that roughly half of employees feel like they can’t trust their boss. So how does a lack of trust and communication affect a company’s overall health?

Not fostering a culture of collective collaboration in the workplace tends to have rather dire effects. The overall health of the organization can seriously be affected and the potential ramifications can easily escalate to include: loss of team momentum and motivation, increase in time focused on training replacements and away from important projects, and a decrease in team morale. All of these potential individual and team losses lead both directly and indirectly to loss of capital due to lack of workplace efficiency and productivity which undoubtedly affects your organization’s bottom line.

For me, day to day professional life has way more similarities to military life than I would like to admit.

Part of my personal attraction to working in the world of startups is that it’s amazingly reminiscent of living in the world of small-unit leadership in the United States Marine Corps. One minute you’re rolling at break-neck speed to obtain a mission objective and the next, you’re pulling a 90-degree turn into a different direction entirely, all the while pursuing the new objective with as little deceleration as possible.

But how can success in either military or professional role be achieved, especially when the potential for loss of capital (or worse) is magnified by the severity of both situations?

In my experience, success in either realm is best achieved by having a plan and the “rocks” to abandon that plan and strike off in a new direction as the situation dictates. The key in either situation is to make rapid decisions on a moment by moment basis, based solely on the information received.

The key component to the equation is ensuring that the “small-unit” leader is given the appropriate information. Battlefield Intelligence, as we’ve all read, can be cloudy at best, with assumptions and inferences driving many of the decisions of the operation. In small unit leadership, we learn quickly that “intel reports” are relied upon when crafting an initial plan of action, however, trusting that Murphy’s Law will always be in effect, we are also taught that whenever we have a plan, we should have the “situational versatility” to be ready to abandon that plan as quickly as it was crafted.

What does this mean in the business world? Consider that quarterly and annual goals are traditionally based upon past performance, using that data to curate an overall picture of health of the individual, team, department, and the organization as a whole. That information (not only of past performance, but also of extrapolated results) used in the hands of the appropriate individual - or the “professional small unit leader” - allows for the individual to analyze and adjust both their own, as well as their team’s, current course to achieve greater results on an almost instantaneous basis.

This can be seen in Forrester Research’s survey where they found that 40% of organizations with access to data like this saw higher ROI on their investments overall.

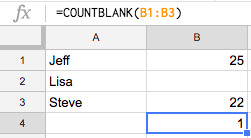

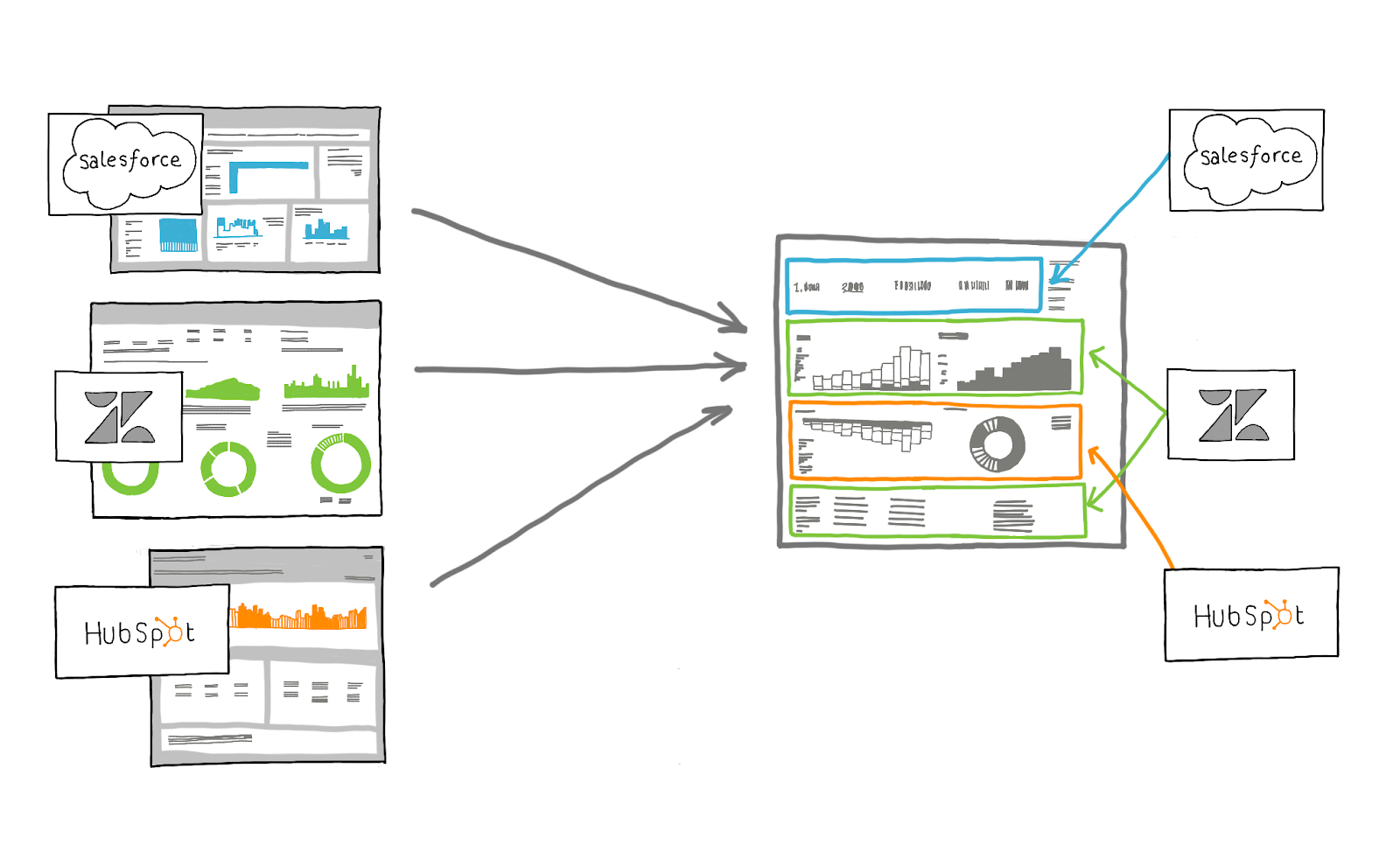

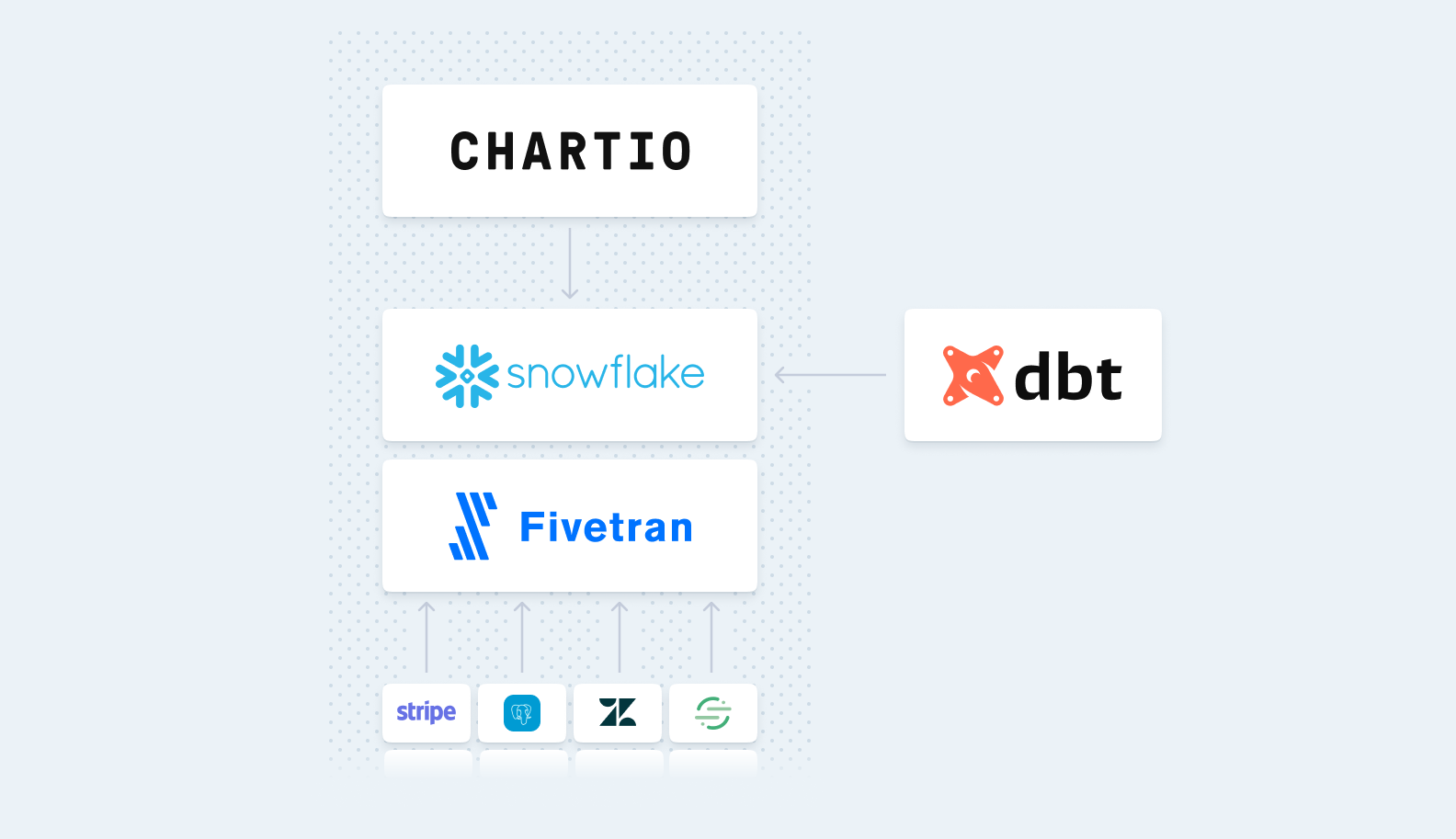

The best way to obtain this necessary information is to empower anyone within the company to easily access their data, analyze it, and determine appropriate conclusions without requiring assistance from an analyst or engineer.

By limiting data access to just the analysts who create reports for the Leadership team’s consumption, “chokes off” the dissemination of real-time information to those who could use it most in order to effect change in the organization in an intelligent and timely manner.

An appropriate analogy of allowing a “military intel report” created by an Intel Officer only for digestion by the General and his staff members applies here with frightening alarm.

If we take the above analogy and compare it to the recommendations of Sturt & Nordstrom (allowing the decision-making process to trickle-down to the individual teams, providing them with the highest quality of intelligence to effect their own course corrections as they see fit), we are allowing teams to take an active part in the ownership of their successes.

By doing this within your own professional organizational structure, you are essentially allowing your “corporate Non-Commissioned Officers” (who usually have the ability to make the best decisions due to their close proximity to the hard data that goes into the intel reports) to drive the success of your company.

Since its inception in 1775, The U.S. Marine Corps has been more than successful in utilizing its brand of small-unit leadership. Why not use business intelligence as your organization’s “intel officer” in order to allow for your organization to adopt its own brand of small-unit leadership in an effort to gain similar results?